The Movement Down Under

“We gain life by looking at life.” Those are the words of Dr. Mardie Townsend, a researcher and associate professor in the School of Health and Social Development at Deakin University in Victoria, Australia, and an important thinker about the importance of the natural world to human development.

She added, in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, “If we see living things, we don’t feel as if we’re living in a vacuum.”

She added, in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, “If we see living things, we don’t feel as if we’re living in a vacuum.”

That sense of aloneness, without kinship in the natural world, is central to the argument that many of us are making these days; that is, if we deny children direct experience with nature, we deny them access to a fundamental part of their humanity.

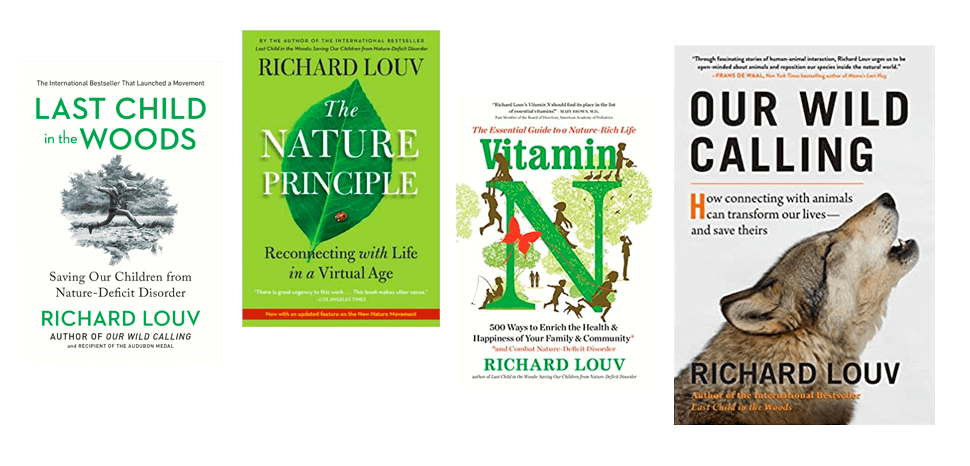

In Last Child in the Woods, I coined the term Nature-Deficit Disorder to serve as a descriptor of the human costs of alienation from nature, not as a medical diagnosis.

That’s one way to look at our lost kinship. Glenn Albrecht, director of the Institute of Sustainability and Technology Policy at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia, has coined a different term, with a related meaning — solastalgia — the unconscious fear of the loss of nature, a peculiar kind of homesickness.

Fortunately, there’s a growing international movement to connect children — and the rest of us — with nature. An appreciation of nature is rooted in the cultures of Australia.

Yet, that country, like the United States, has been battling the problems caused or exacerbated by a sedentary, de-natured life. I’m looking forward this month to my first visit to Australia, to learn about innovative ideas there.

I’ll be meeting and learning from people and speaking in Melbourne, Brisbane, Bendigo, and Perth. Two other Children & Nature Network board members will also be speaking in Australia this month: Dr. Howard Frumkin, at International Congress 2010, Healthy Parks Healthy People, and Brother Yusuf Burgess, at Australia 2010.

In recent articles for Australia’s Active Education Magazine and Web Child (Australia Child Publications), I made the case that some of the best work on this issue is being conducted in Australia. Some examples of research there:

-

- Researchers found a relationship between more time spent outdoors and a lower presence of myopia (near-sightedness) among 12-year-olds in Sydney. The study, reported in the journal Ophthalmology, found that 12-year-olds with the highest levels of near-work activity and lowest levels of outdoor activity were two to three times more likely than their peers to develop myopia.

- A 2009 policy brief from the Centre for Community Child Health, Television and Early Childhood Development, states that young Australian children spent more time television-watching than in any other activity (aside from sleep). Many Australian children live in households where the TV is on nonstop, as a babysitter. (In the U.S., a new Kaiser Family Foundation study found that young people age 8-18 spend more than 53 hours a week plugged into electronic media.)

- Kathleen Bagot, of the School of Psychology, Psychiatry and Psychological Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, has investigated the effects of green play on children. Her study suggests that the higher the level of vegetation around the school, the more highly children rate that environment as restorative. “Greener playgrounds elicit fascination, which is an effortless type of interest, rather than concentration, which can be hard work,” Bagot has explained.

- Researchers at the University of New South Wales found that community gardens were effective in promoting neighborhood renewal in public high-rise housing estates in inner Sydney, and determined that the gardens created a great sense of belonging, friendship and generosity amongst the gardeners and a sense of community on the estates. They were also found to break down cultural barriers as well as promote physical activity and good nutrition principles.

One of the most useful documents on the importance of nature to people is Healthy Parks, Healthy People, a 2008 comprehensive review of relevant literature conducted by researchers at Melbourne’s Deakin University in cooperation with Parks Victoria. At the end of the report is an annotated list of the main benefits to the health and well-being of individuals that arise from contact with nature.

The issue of nature-deficit disorder is also getting more media attention in Australia. This month, in the national newspaper, The Age, environmental reporter Peter Ker reported on the disconnect between children and nature — and the frictions that sometimes emerge when somebody tries to do something about it.

He described how, in Melbourne, plans to establish a community garden within one park sparked local anger. One group of locals wanted the space to grow plants, while others saw the move as a reduction of existing park space for the benefit of few.

With that controversy in mind, Deakin University’s Mardie Townsend suggested to Ker the scouring (of) the urban environment for places to establish new parks and community gardens, including taking advantage of laneways, disused blocks of land and river frontages that are unsuitable for housing developments.

In the long term she added, private companies could turn some of their land into public recreation spaces. “Think of a place like Chadstone [shopping centre], where they have miles of car-parking and have two or three layers. Why not make the top one a [nature] park, which keeps everything cool under that roof and provides a wonderful open space for people,” she told Ker. “People are far more likely to go to Chadstone if there’s a nice park there, where they can sit and have their lunch before going in to shop, so it becomes an economic attractor to business.”

I love that idea. It’s a good companion to the button parks that the Children & Nature Network would like to promote in the U.S. and other countries. Nature shouldn’t just be an exotic adventure, but a place down the street, or in our own yards. Why? As Dr. Townsend said, “We gain life by looking at life.” And touching and holding and hearing it, by using all of our senses in nature. This is the life our children deserve, in every country, on every continent.

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Commentaries on the C&NN website are offered to share diverse points-of-view from the global children and nature movement and to encourage new thinking and debate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of C&NN. C&NN does not officially endorse every statement, report or product mentioned.