NATURAL TEACHERS: 10 Ways You Can Add Vitamin “N” to your Classroom & Beyond

Not long ago I met some dedicated young women who were doing their student teaching at an impressive nature-based preschool. They made it clear that they’d love to pursue careers at similar schools. But they were discouraged about the prospects. Despite growing demand from parents, the number of nature-based preschools remains relatively low.

Not long ago I met some dedicated young women who were doing their student teaching at an impressive nature-based preschool. They made it clear that they’d love to pursue careers at similar schools. But they were discouraged about the prospects. Despite growing demand from parents, the number of nature-based preschools remains relatively low.

“Is there a business school at your university?” I asked. Yes, they said. “Have the business school and your education school ever considered working together to prepare future teachers to start their own preschools?” The students looked at each other. They had never heard of such a thing. Nor had the director of the preschool.

Why not?

Probably because it doesn’t exist. Bringing more nature experiences to education will be a challenging task, and teachers can’t do it alone. Higher education, businesses, families and the whole community must become involved. That’s where the growing children and nature movement comes in. If, as an educator, you’d like to join or help lead the movement, here are a few ways to get started in your own school and beyond:

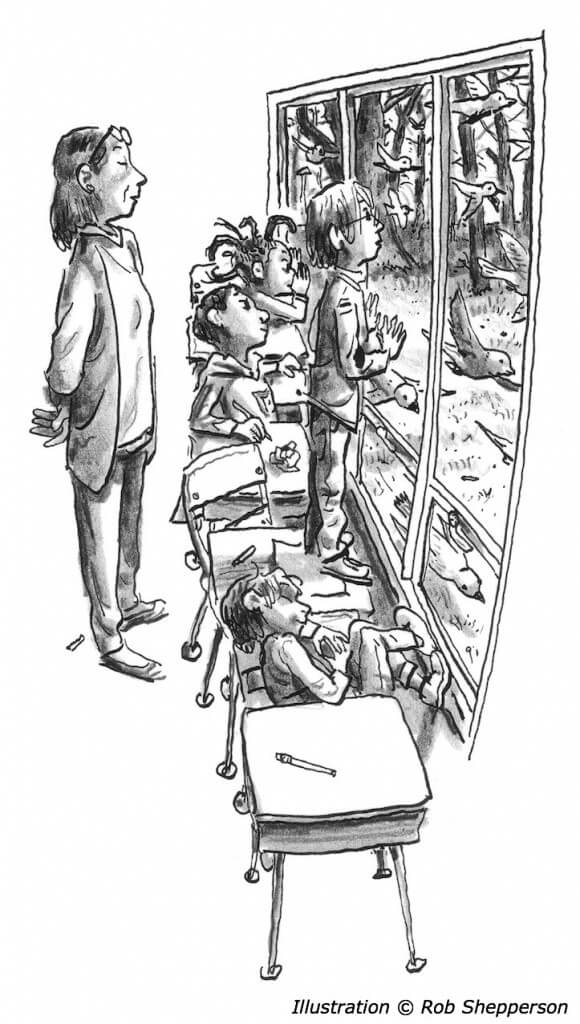

1. Get to know the research. Environmental literacy is essential, but that’s only part of the story. A growing body of evidence suggests that time spent in more natural environments (indoors or outdoors) can reduce the symptoms of attention disorders, and improve cognitive functioning as well as creativity, socialization and mental and physical health. Abstracts and links to original research for more than 200 studies on children and nature can be found at the Children & Nature Network (C&NN) Web site.

2. Join the Natural Teachers Network. “What teachers need to do is network on these issues, get ideas from each other, gripe about what is not working, and brainstorm solutions,” says Tamra L. Willis, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Graduate Teacher Education Program at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia. “There are many challenges related to taking kids outdoors, such as curriculum/standards integration, discipline, materials management, safety, etc. By networking, teachers can share ideas, support each other, and know they are not alone.” Here’s how to join C&NN’s Natural Teachers Network. And download the free Natural Teachers eGuide, which describes programs that your school can emulate.

3. Teach the teachers. Many teachers feel inadequately trained to give their students an outdoors experience. In challenging economic times, community resources may be tapped. For example, many wildlife refuges provide professional development programs that have been correlated to public school curriculum standards. But long-term progress will depend on higher education and the incorporation of nature experience into teacher education curricula. Helping lead the way, Mary Baldwin College offers one of the nation’s first environment-based learning (EBL) graduate programs designed specifically for educators.

4. Create a Teacher Nature Club. Robert Bateman, the famous Canadian wildlife artist, suggests that teachers create their own clubs that would organize weekend hikes and other nature experiences for teachers. Such clubs would not only encourage teachers experienced in the natural world to share their knowledge with less-experienced teachers, but would help improve the mental and physical health of teachers. These experiences can be transferred to the school. (Added note: one study shows that teachers who get their students outside are more likely to retain their enthusiasm for teaching.)

5. Green your schoolyard. Studies suggest that school gardens and natural play spaces stimulate learning and creativity, and improve student behavior. To get started, download the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Schoolyard Habitat Project Guide. Tap the knowledge of such programs as Evergreen in Canada, and the Natural Learning Initiative in the United States. Also, see a worldwide list of schoolyard greening organizations, including ones in Canada, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

6. Bring nature to the classroom. Start a Salmon in the Classroom project or similar endeavor. In Washington State, participating students in over six hundred schools have received hundreds of hatchery eggs to care for in classrooms. Students learn about life histories and habitat requirements and later release the salmon into streams they have studied. Similar programs exist in other states and countries, including Alaska and Canada. (Some schools, worried about salmonella contamination, don’t allow any animals in classrooms. Still, hands-on nature teaching can offer teaching moments, such as: Wash your hands.)

7. Create nature-based community and family classrooms. An outdoor classroom is much less expensive than building a new brick-and-mortar wing. Schools, families, businesses and outdoor organizations can work together to encourage parents to create family nature clubs, introduce students to nature centers and parks, and sponsor overnight camping trips. Or, school districts can follow Norway’s lead and establish farms and ranches as “the new schoolyards,” not incidentally creating a new source of income to encourage a farming culture.) See the Farm-Based Education Network.

8. Help start a nature-based preschool or charter school. Help increase the number of nature-based preschools as well as public, charter, or independent K-12 schools that place community and nature experience at the center of the curriculum. Resources include Green Hearts and Antioch’s Center for Place-based Education.

9. Establish an eco club. One example: Crenshaw High School Eco Club (led by the remarkable natural teacher Bill Vanderberg), has been among the most popular clubs in the predominately African-American high school in Los Angeles. Students have gone on weekend day hikes and camping trips in nearby mountains, and on expeditions to Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks. Community service projects have included coastal cleanups, nonnative invasive plant removal, and hiking trail maintenance. Past members become mentors for current students. Student grades improved. Lives were changed. To learn more, see the CBS Early Show report on Crenshaw’s Eco Club.

Unfortunately, Vanderberg has been transferred to another school, and the Crenshaw club no longer officially exists. Plans are afoot to revive it, in a new form outside the school. Which brings us to the next point.

10. Help grow the children and nature movement. While educators can’t change society alone, the truth is that too many schools and school districts fail to start or support good programs to get kids outside. That’s one reason why the regional and state No Child Left Inside campaigns around the country are so important: by building community support, they bring social and political heft to the table. These campaigns, especially with teacher support, also encourage parent-teacher groups can support schools and educators financially and by presenting annual Natural Teacher awards to educators who have engaged the natural world as an effective learning environment.

Just think what teachers and other educators could accomplish with a little help from, say, business schools — and from the rest of us.

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Commentaries on the C&NN website are offered to share diverse points-of-view from the global children and nature movement and to encourage new thinking and debate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of C&NN. C&NN does not officially endorse every statement, report or product mentioned.