PEACE LIKE A RIVER: There’s a Time for Hyper-vigilance and a Time to Pay a Different Kind of Attention

Chased by an unending stampede of 2,000-pound automobiles and 4,000-pound SUVs, we cocoon inside our homes. The assault continues. Unsettling, threatening images charge through the television cable and overwhelm us. Hyper-vigilance trumps mindfulness. Where do we find respite? The poet Wendell Berry offers direction:

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be . . .

I come into the peace of wild things . . .

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

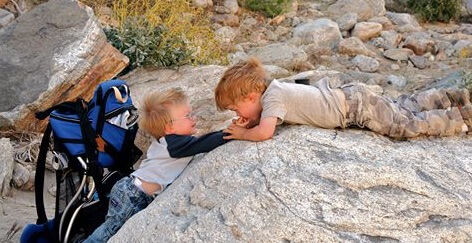

Berry found peace by going to “where the wood drake/rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds…” As a boy, I found peace in the woods behind a suburban tract, when life at home became too difficult, too loud, too much. I found it sitting beside a creek, holding as still as I could, waiting for the leopard frogs to reappear, like ghosts.

Interviewing children and adults for the two recent books, I heard that theme often. I visited my own grade school, in the same classroom where I had once daydreamed while watching the spring branches wave and bow. There, as an adult, I listened to a young girl say softly, firmly: “When I’m in the woods, I feel like I’m in my mother’s shoes. It’s so peaceful out there and the air smells so good. I mean, it’s polluted, but not as much as the city air. It’s like you’re free when you go out there. It’s your own time. Sometimes I go there when I’m mad — and then, just with the peacefulness, I’m better. I can come back home happy, and my mom doesn’t even know why.”

If we’re lucky, these places remain available in our hearts. A psychiatrist who works with children with the symptoms of ADHD related how he sometimes slides into mild depressions. “I grew up fly-fishing in Michigan, and that was how I found peace as a child,” he said. “So, when I begin to feel depressed, I use self-hypnosis to go there again, to call up those memories.” He calls them “meadow memories.” We can create new meadow memories. Tina Kafka, a San Diego teacher, described the impact of a new school garden: “The garden has been much more than simply planting vegetables and taking care of them … When we go to the garden as a class at the end of the day, there is a strong feeling of shared joy and peace no matter how hard the day has been.

In these times of Sandy Hook and Columbine, such talk of meadow memories and the peace of wildness may seem beside the point. Or frivolous. Erring on the side of fear seems to make more sense.

But ongoing research suggests just how restorative those memories can be, how vital they are to a child’s or an adult’s resilience. As I’ve reported elsewhere, earlier studies have suggested a variety of benefits, among them: children who spend time in natural areas show reduced symptoms of ADHD; people who live in proximity to more natural areas produce less cortisol, a stress hormone. And parks with the highest biodiversity offer the most psychological benefits to human beings.

Many other studies point in the same direction, and a new pilot study, published in The British Journal of Sports Medicine, takes science another small step. Researchers in Edinburgh, Scotland used portable EEGs, connected to backpack computers, to measure the brain waves of young adults as they walked through three environments: a pedestrian-friendly historical urban district with light car traffic, a commercial district with high traffic, and a park-like setting. Guess which environment calmed the walkers.

In so many ways, however, society seems to be walking backwards — trusting only the electronic or pharmaceutical fix. Just this morning, The New York Times reported that “nearly one in five high school age boys in the United States” has received a medical diagnosis of ADHD, fueling growing concern that the diagnosis and its medications “are overused in American children.” Why the rise? Over-diagnosis? Or an actual increase in symptoms, which may be due to any number of causes, from the neurological to radical changes in childhood?

There’s a time for hyper-vigilance and there’s a time to pay a different kind of attention. In a recent op-ed, Larry Rosen, M.D., a champion of the children and nature movement, shared this definition of mindfulness from The Three Questions, a children’s book based on a story by Leo Tolstoy: “Realize that the most important time is now, the most important person is the one you’re with and the most important thing to do is what are doing right here, right now… that you will never make all the stress in the world disappear….Take time to look someone in the eyes, listen to her story, and let her know that you hear her. Be willing to sit in the mud until it settles and the water clears.”

The path through the woods is not the only route to mindfulness. And nature experience is no panacea. But our kids deserve a break. So do we. To create meadow memories that can last a lifetime, we can start by taking our children and grandchildren on a hike. We can help plant school gardens, rethink the environments of our neighborhoods, prescribe nature, and much more. Even as we debate gun control and a hundred other issues, we can create a more peaceful life for our children — and at least for a while rest in the grace of the world. We can do this.

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Commentaries on the C&NN website are offered to share diverse points-of-view from the global children and nature movement and to encourage new thinking and debate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of C&NN. C&NN does not officially endorse every statement, report or product mentioned.