WELCOME TO THE NATURAL LIBRARY: The Essential Role of Libraries in Creating Nature-Rich Communities

Libraries exist in every kind of neighborhood; they already serve as community hubs; they’re often supported by Friends groups; they have existing resources (nature books); they’re often more flexible than schools; they’re known for being safe—and they’re a perfect, if unexpected, institution to connect people to nature.

As a parent, teacher, community—or, of course, librarian, you can build community support for turning a local and regional library into a Natural Library (or Naturebrary or Nature-Smart Library, as some folks call libraries that maximize natural elements).

Here are some suggestions for what parents, conservation groups, librarians and others can do to create nature-smart libraries, drawn from St. Paul and other cities.

Design or remodel libraries with the natural world in mind.

Design or remodel libraries with the natural world in mind.

The Sun Ray Natural Library Project’s pioneering renovation project, designed with the help of C&NN board member and architect Mohammed Lawal, includes natural elements throughout, including green spaces inside and in an adjacent park, an outdoor reading garden, wildlife-friendly plants, rain gardens, and dozens of newly planted trees. There’s also a children’s “Nature Nook” inside the library with interactive wildlife features and doors to the children’s outdoor reading garden. There will be a public art installation there called “House Trees” where little houses will be placed up in the air on artistically rendered tree branches.

Work with librarians to create outdoor reading areas on library property.

The Middle Country Public Library in Centereach, New York, created the Nature Explorium, converting an adjacent five-thousand-square-foot area into an outdoor learning environment, “including a climbing/crawling area, messy materials area, building area, nature art area, music and performance area, planting area, gathering/conversation place, reading area, and water feature,” reports American Libraries magazine. Kids are watched by library staff, and every child is required to have a caregiver on the grounds. The Nature Explorium was immediately popular and even attracted some new donors

Think outside the library grounds: Storytime Trails and Book Trees.

Think outside the library grounds: Storytime Trails and Book Trees.

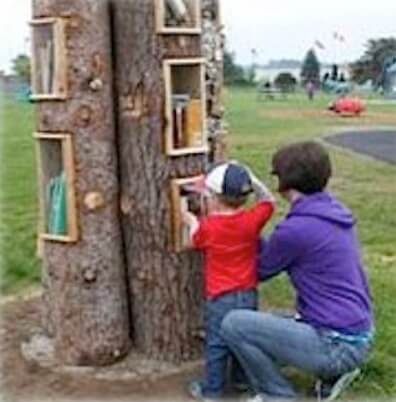

The Petawawa Library/Parks and Rec partnership also created a Storytime Trail. “Children start walking at the beginning of one of our trails, read the first page of a book with their parents, continue another 100 feet to find the second page and continue along the trail until they have read a good portion of the book,” report Kelly Thompson and Colin Coyle, who represent the library and parks departments. “The Library side of the project promotes literacy while the Recreation side of walking to each page gets them active outdoors. We couldn’t dream of a better match.” They also have created “book trees. “In our local playground, a cluster of five trees have been used in the design of a free outdoor library (the trees used were downed in a microburst). The concept is to “take a book, leave a book, and share a book.”

Offer outdoor gear for checkout by children and others.

Some libraries, like those in Petawawa, are already checking out such outdoor gear as fishing rods, snowshoes, GPS units (for outdoor geocache hunts for treasures hidden by library staff members across town). A library-based snowshoeing program is so popular that there’s a waiting list. With the help of parents, schools, and local conservation organizations and outdoor recreation companies, libraries can assemble loanable daypacks containing binoculars, compasses, safety kits, guides to hiking trails and local flora and fauna, and other regional nature information. Local PTAs and PTSAs could help with volunteers and raising funds for this and other Natural Library offerings.

Build bioregional identity and regional biodiversity.

Build bioregional identity and regional biodiversity.

Offer a special section in the library for these books, and Friends of the Library groups can stock the library book-nook stores with nature books, especially ones about the local region. Natural Libraries can provide a meeting place for people who want to explore and discuss the nature of their own region. They can organize lectures and convene groups of architects, urban designers, educators, physicians, birders, and many others to plan the re-naturing of the surrounding community. Natural Libraries can also help create neighborhood butterfly zones—or a national homegrown park—beginning on the library’s own grounds. They can increase backyard biodiversity by partnering with ntural history museums and botanical gardens. For example, libraries could hand out free packets of seeds to families who want to help bring back butterfly and bird migration routes.

Use tech to expand the constituency for libraries, parks, and nature.

Antje Dun, chief librarian for the Australian Conservation Foundation, offers these suggestions: spread the word through a Pinterest page or Twitter hashtag devoted to Natural Libraries; set up a website; build a community of natured librarians using Facebook; create an online newsletter with project topics for natured libraries, such as seed banks, promoting your bioregional identity, nature backpacks, outdoor reading spaces; create a YouTube channel, and ask librarians and library users to make and post videos about Natural Libraries and their activities.

Help libraries build new partnerships with nature-focused and family-oriented organizations and diverse cultural groups.

Help libraries build new partnerships with nature-focused and family-oriented organizations and diverse cultural groups.

A library is a perfect place to convene parks departments, conservation groups, natural history museums, schools, botanical gardens (especially horticultural libraries), and local businesses (particularly from the outdoor industry) to plant the seeds of environmental literacy. In turn, these organizations can promote the library, and grow local support for the library’s financial needs. The Sun Ray library currently conducts family reading hours in Hmong, Spanish, Somali, and English, and hopes to draw on the rich nature traditions in those communities. Libraries can also convene family nature clubs: multiple families that band together to organize nature outings. Also, by encouraging the growth of family nature clubs, Natural Libraries will not only help families get outside but will be building a widening constituency to support libraries generally.

Parents and other community members can work for nature-smart libraries through a Friends of the Library group.

Support your local Natural Librarian. If you’re not already a member of a Friends of the Library group, join and build community support for bringing more nature into the library and more library services into nature. If there isn’t a Friends of the Library organization attached to your local library, create one—and start a Natural Library committee. Learn more about Friends groups at the United for Libraries website.

Lend your support to nature-smart librarians across the country.

Reaching beyond localities, we need national or international campaigns to bring together librarians, publishers, parents, literacy experts, and other stakeholders to devise a campaign to naturalize libraries across the country and around the world. As Cicero said, “If you have a garden and a library, you have everything.” Or almost.

Note: This post has been updated from the original which was published in June of 2015.

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Commentaries on the C&NN website are offered to share diverse points-of-view from the global children and nature movement and to encourage new thinking and debate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of C&NN. C&NN does not officially endorse every statement, report or product mentioned.