BACK TO THE SCHOOL OF THE FUTURE: The Real Cutting Edge of Education Probably Isn’t What You Think It Is

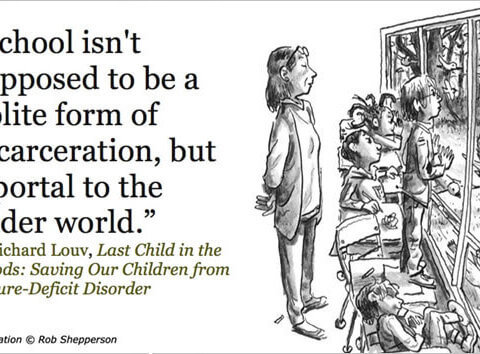

In recent decades, many of America’s school districts have favored reduced recess, fewer field trips, longer hours sitting at desks, more tests, and more computers, iPads and even video games used as teaching tools in classrooms.

Consider what may be the ultimate high-tech school: AltSchool Brooklyn, a pre-K to eighth-grade private school. As Rebecca Mead writes in The New Yorker, it “does not look like a traditional educational establishment. There is no playground attached, no crossing guard at the street corner, and no crowd of children blocking the sidewalk in the morning. The school is one floor up, in a commercial building overlooking Montague Street.”

Inside the school, the cutting edge is sharp indeed. Students are issued tablets in pre-K. “AltSchool embeds fish-eye lenses in the walls of its classrooms, capturing every word, action, and interaction, for potential analysis.” The teacher of the future will be transformed, into a data-enabled detective” according to one of the school’s founders. “Retroactively omniscient,” is how another AltSchool leader, formerly a Google employee, put it.

The good news, apparently, is that testing, as we know it, will go away. The weird news: we won’t need traditional testing because the machines will be watching our kids all the time — every keystroke will be monitored and measured, every restless wiggle, every eye that wanders into a daydream, every sidelong glance at a tree beyond the window, moving in the wind.

Some digital technology is effective in and outside the classroom. But how far do we really want to go in that direction? As a new school year begins, a refresher on what may be the real cutting edge of education is in order.

Around the country and the world, a countertrend to Silicon Faith is building – based not on a rejection of educational technology, but on a growing hunger for a better balance between the virtual and the real.

As I reported in Last Child in the Woods, and earlier in this space, evidence supporting nature-based, place-based education or experiential learning (as this approach is variously called) has been building for decades. Gerald Lieberman, an internationally respected education expert, helped produce a 2002 report for California report called “Closing the Achievement Gap.” He worked with 150 schools in 16 states for 10 years, identifying model programs in place-based education or experiential learning, examining how those students fared on standardized tests.

As I reported in Last Child in the Woods, and earlier in this space, evidence supporting nature-based, place-based education or experiential learning (as this approach is variously called) has been building for decades. Gerald Lieberman, an internationally respected education expert, helped produce a 2002 report for California report called “Closing the Achievement Gap.” He worked with 150 schools in 16 states for 10 years, identifying model programs in place-based education or experiential learning, examining how those students fared on standardized tests.

The findings were stunning. Students in the schools achieved gains in social studies, science, language arts and math; improved their grade-point averages; and developed skills in problem-solving, critical thinking and decision-making.

Another pioneer in the philosophy of place-based education, David Sobel, conducted an independent review of “Closing the Achievement Gap” and other studies. His conclusion? When it comes to reading skills, place-based education should be considered “the Holy Grail of education reform.” Still, for years, Lieberman’s report was virtually ignored by the education establishment. Among the possible reasons, the body of evidence is relatively new; and most of the studies of health and education showed correlation, not necessarily cause.

Today, longitudinal studies are offering encouraging data. A six-year study of 905 public elementary schools in Massachusetts found that third-graders got higher scores on standardized testing in English and math in schools that had closer proximity to natural areas. Likewise, preliminary findings of a 10-year University of Illinois study of more than 500 Chicago schools, comparing green schools with more typical schools, indicate similar results, especially for the most challenged learners.

Today, longitudinal studies are offering encouraging data. A six-year study of 905 public elementary schools in Massachusetts found that third-graders got higher scores on standardized testing in English and math in schools that had closer proximity to natural areas. Likewise, preliminary findings of a 10-year University of Illinois study of more than 500 Chicago schools, comparing green schools with more typical schools, indicate similar results, especially for the most challenged learners.

As it turns out, greening schools may be one of the most cost-effective ways to raise student test scores.

An additional approach is the use of nature preserves by environment-based schools, or the inclusion of established farms and ranches as part of these “new schoolyards.” Norway’s departments of Education and Agriculture support partnerships between educators and farmers to revamp school curriculum and to provide more direct outdoor experience and participation in practical tasks. A purely natural setting isn’t required. Natural learning environments can be created in a forest or in an urban neighborhood, especially if it’s graced with a little nature.

None of this is news to educators in Finland. In the early 1970s, after decades of war and Russian occupation, Finnish schools were in bad shape. But, during past decade or two, while the US began to fall behind, Finland’s scores in math, science and reading have consistently been at or near the top, as measured by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Year to year, Finland typically ranks first in PISA’s measure of “study effectiveness.” The reasons for these gains are complex, but in Finland, outdoor recess, often held in natural spaces, is considered nearly as crucial to academic success as literacy.

When he first visited Finland, Tim Walker, an American teacher teaching in that country, was skeptical. In a 2014 article in The Atlantic, eloquently described the difference that periods of nature play made in his own students. “Normally, students and teachers in Finland take a 15-minute break after every 45 minutes of instruction,” he wrote. “During a typical break, students head outside to play and socialize with friends while teachers disappear to the lounge to chat over coffee…Once I incorporated these short recesses into our timetable, I no longer saw feet-dragging, zombie-like kids in my classroom.” Most importantly, he reported, after their 15-minute outdoor breaks, his students “were more focused during lessons.”

Walker’s observations mirrored the growing body of research that points to a relationship between more natural learning environments and reduced symptoms of Attention Deficit Disorder, stress reduction, lower burnout rates for teachers, and increased civility.

In the United States, exciting developments include the dramatically increasing popularity of nature-based preschools or forest schools, such as Raintree School in St. Louis, Missouri, as well as nature-based public schools, including the exceptional Chattahoochee Charter School in Georgia. We also see the national movement to build natural play-spaces at schools, serving both children and the surrounding neighborhoods. “Natural spaces and materials stimulate children’s limitless imaginations and serve as the medium of inventiveness and creativity,” says Robin Moore, an international authority on natural school design, who heads the Natural Learning Initiative. New schools must be designed with nature in mind, and old schools can be refitted with playscapes that incorporate nature into the central design principle. And the field of animal-assisted therapy, including in schools, is also growing rapidly.

What if nature-based learning environments were part of an even grander goal? In New Zealand, the government now prioritizes measures of mental health over economic growth, in education and other sectors. As reported here, proponents, including Lord Richard Layard, a professor from the Centre for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, argue that this new direction would stimulate economic growth by increasing happiness and productivity.

Surely in the age of biodiversity collapse, the climate emergency and nature-deficit disorder, we need new nature-based models for education and community – ones that help produce a gentler world for the children of all species.

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Other reading and viewing:

- CBS This Morning segment on Chattahoochee Charter School.

- At “Nature Preschools,” Classes are Outdoors: Education Week

- Education and the Environment: Creating Standards-Based Programs in Schools and Districts by Gerald A. Lieberman

- What if schools valued wellbeing more than results?

- Do Experiences With Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship

- How Finland Keeps Kids Focused Through Free Play

- Children’s Special Places: Exploring the Role of Forts, Dens, and Bush Houses in Middle Childhood

- Edweek: Is Less Classroom Time, More Outdoor Play the Secret?

- The Green Schoolyard Movement: Gaining Ground Around the World

- The Hybrid Mind: The More High-Tech Education Becomes, The More Nature Our Children Need

- Back to School, Forward to Nature: Ten Ways Teachers Can Fortify Their Students With Vitamin N

- Teaching Kids to Be Nature Smart, National Wildlife Federation

- The American Academy of Pediatrics report on the importance of recess

Additional Resources

- For some of the most recent research on the educational benefits of nature exposure, see C&NN’s Research Library, and sign up for the Children & Nature Network Research Digest.

- Download the Natural Teachers eGuide.

- C&NN’s Green Schoolyards for Healthy Communities Initiative.

- Green Hearts

- National Wildlife Federation Tools and Resources for Teachers

- The International Association of Nature Pedagogy, launched March 19, 2014

- Nature Based Leadership Institute, Antioch University New England

- Nature Preschools and Forest Kindergartens: The Handbook for Outdoor Learning

- The International Association of Nature Pedagogy, launched March 19, 2014

- North American Association for Environmental Education

- National Environmental Education Foundation (NEEF)

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Good Morning!

I am a preschool school special ed teacher in a VERY dense, urban city. I am 27 years young so adapting to virtual learning was not very hard from a technology perspective. As for not seeing my students in person and giving them the physical oppourtunities to learn I have been looking at what I can do to make virtual learning more meaningful and purposeful and I always come back to nature. In this rapid age of technology it is hard to see myself as a public school teacher for much longer. I am looking for other options to teach children through nature and just pure passion. I came across your book “Last child in the Woods” and have already ordered it. Thank you for being a voice for those teachers that feel alone in a now, very scripted career.