RAISING WILD KIDS: Why I Endanger My Kids in the Wilderness

A glacial wind pours through a snowy pass in the remote mountains of Norway’s Jotunheimen National Park. Virtually devoid of vegetation, the terrain offers no refuge from the relentless current of frigid air. Some of the troops are hungry, a little tired, and grumpy; mutiny doesn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility, so I don’t want to add “cold” to their growing list of grievances. I coax everyone to push on just a little farther, down out of the wind to a sun-splashed, snow-free area of dirt and rocks for lunch.

But I don’t like the looks of the steep slope we have to descend. Blanketed in snow made firm by freezing overnight temperatures, and littered with protruding boulders, it runs hundreds of feet down to a lake choked with icebergs—in mid-July. A trench stomped into the snow by other trekkers diagonals down to our lunch spot. It’s well-traveled, but someone slipping in that track could rocket downhill at the speed of a car on a highway. I turn to our little party—which ranges in age from my nine-year-old daughter to my 75-year-old mother—and emphasize that we have to proceed extremely carefully.

We inch our way across a span of snow broader than a football field is long. Within twenty feet of the safety of the dirt where we intend to stop, I hear my wife behind me shriek, “Nate!” And I spin around to see my 11-year-old son sliding downhill, accelerating rapidly.

By sheer luck—or perhaps just because he weighs so little—he stops abruptly about 30 feet below us, caught on the lip of a moat that has melted out on the uphill side of a boulder. (With a little more speed, he might have slammed into that boulder, miles from the nearest road and many hours from the nearest emergency room.) I tell him to remain still, then usher everyone to the lunch spot and kick steps into the hard snow down to Nate to lead him to safe ground.

I hesitate to share that story because some people will read it and judge me a bad parent who willingly places his children in harm’s way. Some parents may see it as validation for their fear of taking kids out into nature. I’m a father (and not mentally unbalanced, honestly); I understand that protective instinct. I’ve also seen how quickly everything can go wrong in the backcountry—a few times, in fact, which is a few too many. But seeing danger suddenly grab one of my kids and hurl him down a mountainside felt like simultaneous blows to my head and heart. For the rest of that trip, and occasionally since, those three seconds of horror have replayed in my mind, and I’ve chastised myself for not simply guiding my kids and my mom one at a time across that slope (as I did when we continued that descent—uneventfully—after lunch).

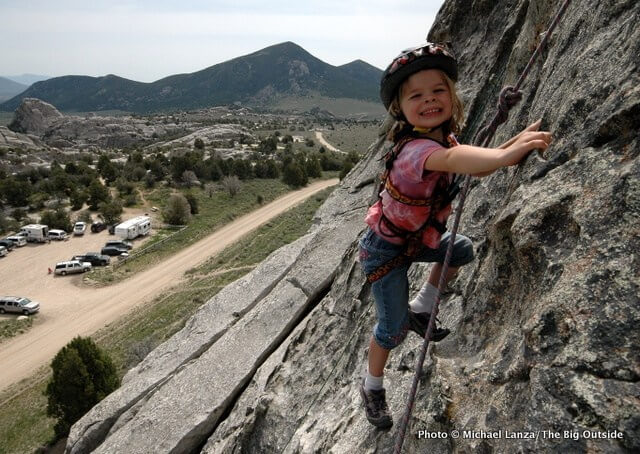

Now, several years after that beautiful, weeklong, hut-to-hut trek in Jotunheimen, my family and the friends who joined us look back on it fondly. In spite of that haunting memory of Nate’s slide and a deep understanding of the inherent risks, I continue to take my kids backpacking into wilderness, rock and mountain climbing, whitewater kayaking and rafting, and backcountry skiing. The reasons for that derive from societal forces as much as personal values, and are as complicated and vexing as parenting itself.

But I’m still not sure what terrifies me more: knowing how close we came to tragedy, or my enduring belief that exposing my kids to this kind of danger is somehow good for them.

I became a father at age 39, on the brink of middle age, and began playing parent by ear with only a vague sense of the melody (which inevitably means hitting a lot of bad notes before finding the right ones). I’d had a good life through my thirties, working as an outdoor writer, spending more days outside every year than many avid backpackers, climbers, skiers, and paddlers spend in 10 years. In some ways, I think it may have been harder to surrender that freedom at that age than it might have been 10 years earlier. Suddenly, the cold reality of fatherhood had taken away my ability to head out anytime the desire hit me.

I saw only one conceivable strategy for preserving my charmed lifestyle—and my sanity: I had to raise my children to love the outdoors as much as I do.

Shortly after my son and daughter came along in the early 2000s, author Richard Louv coined the term Nature-Deficit Disorder in his bestseller Last Child in the Woods, revealing just how little time children in many Western nations spend outdoors. As my kids reached school age, I began to realize how many parents believed—based on overwrought news reports that painted a picture very different from the statistical reality—that child abductors lurked everywhere, making the streets and playgrounds unsafe for children to wander around unsupervised (as if they were, you know, children). Instead, parents actively managed their children’s time through organized sports and music lessons and “play dates” with other kids—which I believe helps foster the impression in kids’ minds that “playing” involves one friend, maybe two or three, not the larger gatherings required for activities like pickup sports games.

It slowly dawned on me how radically the topography of childhood had shifted in the decades since I’d traveled over it.

This post was originally published on The Big Outside.

- Learn more about Mike’s National Outdoor Book Award-winning book, Before They’re Gone—A Family’s Year-Long Quest to Explore America’s Most Endangered National Parks

- Read more of Mike’s writing on his blog, The Big Outside

- CAMPING WHILE PARENTING: A Mother-Son Adventure

- Force of Nature: Putting Women Front & Center Outdoors – REI.com

- Family Nature Clubs

- Nature Clubs for Families Tool Kit

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Michael Lanza’s blog,

Michael Lanza’s blog,