Our Need for Nature in the Time of COVID

Join me in the movement to connect children and nature

Back in June, The New York Times ran this headline: “Nature Deficit Disorder is Really a Thing,” adding, “Children’s behavior may suffer from lack of access to outdoor space, a problem heightened by the pandemic.” The Times got that one right, and we appreciated it.

One of the pleasures for those of us who work with the Children & Nature Network (C&NN) is that we get to meet so many people whose lives and communities have been changed through our shared cause.

We hear from parents who have witnessed the power of nature to help reduce their children’s symptoms of Attention Deficit Disorder and, for some parents, help fight their own depression. We’re inspired by parents who have launched nature clubs to help families get a regular dose of “Vitamin N”—and of course, we meet children. We’ve seen their eyes light up in the presence of a mud puddle or a frog or a star.

We’ve encountered young college students inspired by the children and nature movement to pursue careers in environmental education, outdoor recreation and nature therapy.

We’ve spent time with countless teachers who talk about the impact of outdoor learning and play on their students. As one teacher told me, “When I take my students outdoors, the troublemaker in the classroom becomes the leader in nature. Not just better behaved, the leader.”

And we hear from grandparents who have committed themselves to do everything they can to make sure theirs isn’t the last generation in which it’s considered normal and expected for a child to go outside and lie in the grass and watch the clouds.

“This is fundamentally a movement of people helping people. Of all ages.”

We’ve met conservationists, despairing at the state of the environment, who say they’ve been revived by the children and nature movement. We know pediatricians who write nature prescriptions or incorporate the healing qualities of the natural world into their practices.

We’re working with mayors and other community leaders who are transforming their cities, neighborhoods, and institutions in ways that assure that all children, not just a few, have a chance to read under a tree or see the stars. Today, through the partnership of C&NN and the National League of Cities, 18 major cities are focused on deep systems-level change to improve equitable access to nature, charting a course that can be applied in countless cities and municipalities.

We’ve been inspired by librarians who create “nature smart” libraries with outdoor learning centers and reading areas; and by dramatic growth in the number of nature-based preschools across the nation and around the world.

Through C&NN’s efforts, and the good work of other organizations, the green school yards movement is transforming the school experience, not only for thousands of students but for community members who help create and enjoy these new outdoor spaces. The payoff: healthier families, improved test scores, resilient communities.

“In a few short years, we’ve seen this movement spread around the urbanizing world. This may, in fact, be one of the most effective social movements of our time.”

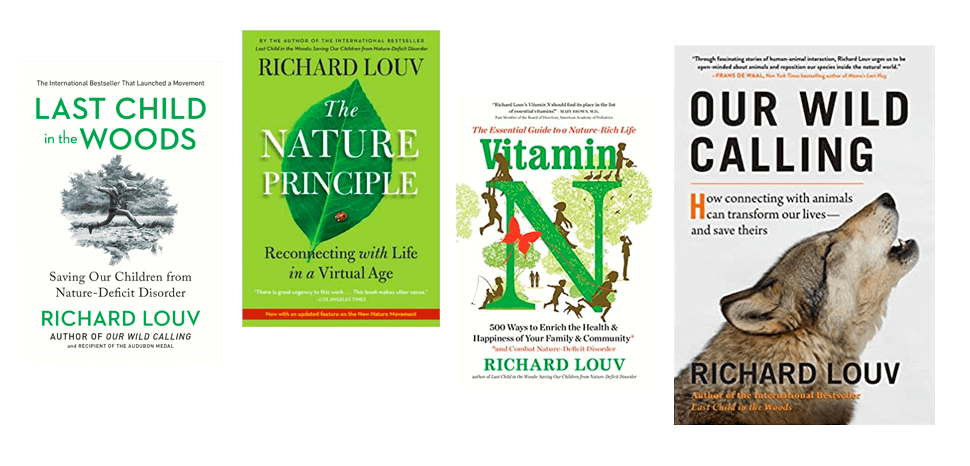

It’s a movement based on a rapidly growing body of research on the benefits of nature connection for physical, mental and cognitive health. When I was writing Last Child in the Woods, published first in 2005, I could confidently cite about sixty studies, pursued by a handful of pioneering researchers. Today, C&NN has assembled an online research library, available free to anyone in the world, offering abstracts of over 1,000 studies, with more added every month.

Now comes COVID, and with it, recognition of what people knew during past pandemics. Outdoor spaces, including outdoor classrooms, can offer more protection from viral contagion and from depression. The pandemic, as tragic as it is, has dramatically increased public awareness of the deep human hunger for nature connection.

Even before we began socially distancing, health professionals worried about an epidemic of human loneliness, which, along with smoking and obesity, is a high-risk factor for early death. Today, families, stressed by fear of the virus, facing economic uncertainty and hardship, find themselves cut off from their usual social circles. They have turned to nature for solace and connection.

Families have rushed to foster pets and they have forged a stronger bond with the animals right outside their windows. In a July op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, I wrote about a woman whose daughter had a strong attachment to a screech owl that lived in a tree outside a bedroom window. Long before the coronavirus, the owl disappeared one day. A few weeks ago, when her family was feeling particularly anxious, her daughter suddenly brightened and shouted, ‘The owl’s back!’” Her young son now rises early to watch the owl, “and the owl watches him,” his mother reports. For this family, nature connection brings “an awareness of something greater.”

No matter what our age, when isolated and on our own, we find ourselves yearning for a horizon of trees, wind across a prairie, and for our extended family of animals.

During lockdown, a friend of mine placed a bird feeder outside her elderly mother’s bedroom window so her mother could be soothed by sparrows, chickadees and doves. My friend reports that she is grateful for “all the fluff and feathers God provides, to be healing for our wounded spirit” — and won’t again take the presence of wild animals for granted.

Some of us are lucky to live in places where connecting to nature is easier. But too many people have too little access to parks, yards or even a tree outside a window.

These inequities may worsen. Economic deterioration now threatens the survival of programs and parks that connect children and families to nature – especially those who otherwise would have little access. While more adults are packing the parks, children are often not with them. We fear that children may be spending even less time in the natural world than before the contagion of COVID-19.

Research tells us that time spent in nature can soften the effects of psychological and physical trauma. In the coming months, as the pandemic-related mental health crisis continues and grows, access to the natural world – to the “fluff and feathers” and an “awareness of something greater” – will be more important than ever.

This is why I ask you to support the Children & Nature Network and other good organizations working to make sure that all children – not just a few – receive the healing gifts of nature. Learn more about our work and please join us today.

3 Comments

Submit a Comment

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

You do not have to be inside to be safe from COVID. Sitting on a porch, under a tree, or just going for a walk will do wonders for your mind and your health. Encourage children to safely venture outside, absorb the sunlight and breath the fresh air. BTW, Don’t forget to join them as well.

This is great advice, David, especially the part about joining children outdoors. Thank you for sharing.

I’m one of those fortunate people whose love of nature began in childhood. Dad took us outdoors in every season for gardening, planting trees, countless projects and lots of fun activities. Mom read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring as soon as it came out and became an early advocate for protecting natural environments. I became involved in environmental education in the mid-1970s and returned to it in retirement in the mid-2000s. John Strickler, Kansas Forestry Service and K-State professor, was an early influence on me, and the Kansas Association for Conservation and Environmental Education (KACEE) that he co-created continues to be an outstanding organization providing ongoing skill-building opportunities for experienced, new, professional, and lay educators.

In 2005, I developed the Learning About Nature Project through the sponsorship of Jayhawk Audubon Society in Lawrence, KS. Creating field trips in the past 16 years for over 10,000 K-7th grade students in Lawrence Public Schools, mainly to teach about wetlands, has given me a wide array of pleasures. High among them has been seeing so many young people evolve within a matter of minutes from perceiving the natural world as dangerous, uncomfortable or boring to realizing it’s much safer (we’re usually the most dangerous organism there) than expected, offers many forms of enjoyment and is full of fascinating ecosystems and organisms—fauna, flora, fungi…

Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods came out around the time I started the LANP, so I heard of it as the project was going through the difficult stages of being implemented. The book gave me encouragement and hope, because there was someone spreading the word at a national—and eventually international—level about the crucial importance of valuing and feeling connected with the natural world. When Cheryl Charles came to Lawrence to facilitate a 2-day conference, I was excited to find how many local organizations were interested in environmental ed of various kinds for children or adults. As teachers experienced the LANP field trips, their reticence to take time for field experiences changed to eagerness, and their skills to incorporate environmental ed activities into their own teaching steadily increased. People of all ages began slowly but surely re-engaging with nature.

There’s no way to adequately convey how thankful I am for the C&NN. I shared Richard Louv’s surprise that there was little research into the value of nature on human well-being at the time we both started efforts to reconnect children with an essential aspect of life so many had barely experienced. C&NN has had a huge role in making EE a research-based, multi-faceted, all-inclusive endeavor that gives teachers, administrators, parents, and others the validation, resources, networking opportunities, moral support, and more needed to create opportunities that make being in nature an integral part of human experience. This was how we lived for most of our species’ existence and, to some extent, it must be again in order to thrive and regain our intimacy with the natural world. We’re not separate, not here to control it, and not more valuable than other life forms. It’s not a “resource” for us to squander until used up. Thank you, Richard Louv, Cheryl Charles and all the others who’ve chosen to take actions intended to renew our essential, integral connection with nature.