Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

It was 2013. I was away from home for a work meeting when Danae called and told me that our daughter, Lydia, had an EEG test scheduled for the following morning. She was three months old at the time. I drove all night to meet my family at the hospital for the appointment.

The next day, we were hopeful throughout the EEG. Even still hopeful when they checked us into the hospital for an emergency MRI. The hospital staff were friendly and professional, friends all pitched in to take care of our oldest son, Jack, and things seemed to be going okay. We waited. Then the neurologist came in to talk about the findings of the MRI. Five brain malformations. Soon after, we were informed that it was very unlikely Lydia would get past the age of seven due to the complexity of her medical condition. In that moment, I realized what true shock felt like. For days, months and years afterward, I can still hear those words as clearly as when I first heard them.

My daughter, Lydia Davison, is now eleven years old. She is gentle, loves to eat lollipops and has a dark sense of humor. All of this shines through despite her undiagnosed condition. Lydia has approximately 100 seizures per day and is currently both nonverbal and mostly immobile. She is learning to use a computer to communicate and uses a wheelchair to get around. I love her for who she is and now think of disability as a natural part of everyday life.

Lydia, age six, with her siblings Jack and Momi, and with her mam and dad. Photo by Mark Davison.

As the dad of a daughter who experiences disabilities and as a professional who has spent his career working in National, state and city parks conserving nature and designing parks, I’ve found my professional and personal life at odds. My career path has focused on park planning, park design, visitor experience, land management and environmental conservation. However, much of the great work I believed I was doing in my job seemed to only create additional barriers for my daughter to access nature, from added steps on trails to inaccessible environmental education programs.

Over the years, Lydia has inspired me to think of and conceptualize accessibility in new ways within my professional role as the park planning manager at the City of Boulder, Colorado. She has been a crucial influence in this journey to ensure that not only she, but all children can universally access the many benefits of being in nature.

Why is nature accessibility important?

Lydia, outside in nature under the dappled shade of trees. Photo by Mark Davison.

The thing Lydia seems to enjoy most is being outside in nature under the dappled shade of trees. She loves bird calls in the early morning, camping in the fresh air and a rough-hewn trail that her chair bounces along on for a fun ride. A growing body of research demonstrates the science behind Lydia’s “good feelings” outdoors. Researchers have been diving ever deeper into how we need a connection to the natural world to thrive. Any Google search on the benefits of nature will reveal hundreds of results demonstrating how being outdoors decreases stress and anxiety, makes you happier, promotes pro-social behaviors and provides an additional wealth of positive physiological and neurological responses to natural environments.

How does ADA enable play yet also limit the experience?

Disability rights are civil rights. After a hard-fought battle, the Department of Justice enacted the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a federal law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability, ensuring equal access and benefits to all people. The law ensures equitable access for people with disabilities in many areas of public life – including outdoor facilities and services through the 2013 Forest Service Trail Accessibility Guidelines (FSTAG) and 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. These standards increase the accessibility of federal, state and city outdoor spaces including parks, green spaces, plazas and streets.

According to ADA standards, playground equipment and facilities constructed or altered on or after March 15, 2012, must include an accessible path from the building or parking lot to the edge of the play area, an accessible path from the edge of the play area to the play equipment and adequate surfacing. Once a child is in the play area, they must be able to access the play equipment by either moving out of their mobility device onto the playground structure (utilizing resources like a transfer station) or by direct play structure access in their mobility device (which may require a ramp).

The image shows an ADA-accessible surface, yet the stairs highlight the frustration a parent and child will feel upon reaching the equipment.

While well-intentioned, ADA standards for playgrounds often fall short of providing genuinely accessible and engaging experiences for children with disabilities. The emphasis on physical access, especially for wheelchair users, while helpful, represents a limited perspective. This narrow focus overlooks the diverse experiences related to neurodiversity and varying physical abilities within the disability community.

One of our major goals with Lydia is to consistently seek out new places beyond the typical ADA-designed paths and spaces, which is possible with a few minor tweaks here and there. Often though, the barriers are just too great to enable Lydia to have equitable access to parks and playgrounds in the same way her two siblings can.

In one instance, I took Lydia and her younger sibling, Momi, to a nearby park. While Momi ran to the swings, I pulled Lydia’s chair onto a patch of concrete and whizzed her around in a circle to make her smile. However, Momi soon began to cry for assistance on the swings, and I couldn’t reach her with Lydia, as the playground surface was covered in bark mulch, which bogs down her wheelchair. As we ended our playtime, Lydia needed to be changed – but the changing tables in the park bathrooms did not accommodate a 60-pound person. Forced to change her in the trunk of my car, we were exposed to other parents and people heading into the park – it felt shameful. When we finally drove home, I was defeated and both children were in tears. A simple park trip can be filled with barriers that make parents and children experiencing disability feel a painful, sometimes desperate, isolation.

Siblings freely exploring a trail, with one, who has low vision, joyfully galloping along. The parents have weighed the risks against the benefits of play, learning and sheer enjoyment.

While many outdoor spaces now include ADA paths, these often turn out to be flat, short, and boring. It’s not anyone’s fault – this is the only way designers can meet federally imposed standards for ADA that our forebears campaigned for back in the sixties and seventies. ADA, while invaluable in its time, hasn’t adapted to the changing needs and the growing number of children with disabilities participating in outdoor activities, a stark contrast to the situation 30 years ago.

Here’s an example: In Boulder, we aimed to establish an accessible trail from a popular trailhead to a bridge that was a half mile away. Unfortunately, the endeavor had unintended consequences. The trail design turned out to be monotonous and uninspiring. When you reached the end of the ADA-compliant route only to see the trail continue beyond the bridge, it was an insulting conclusion to someone experiencing disability. Moreover, the bridge’s dead-end offered the worst view along the trail. Despite following ADA and FSTAG guidelines for safety, flatness and visibility, the outcome was a dull, brief and unappealing destination.

Building a more diverse sensory experience

Observing Lydia’s lived experience and spending time with many of her friends in the disability community has deepened my understanding of how ADA regulations enable access to recreation through predominantly just one sense: sight. Although science has demonstrated that there are nine identified human senses, modern society no longer engages all nine regularly. As a result, we have consistently designed public spaces that focus on the use of our eyes and legs, which ultimately limits all of us in terms of the types of experiences we can enjoy.

New chairs designed with lightweight materials, suspension and low centers of gravity enable you to get to most places without the need for a 10ft wide concrete path that, though well-intentioned, takes away from your ability to support your child in connecting with nature. Photo by Mark Davison.

Lydia does not have the use of her eyes or legs to navigate this world, but over the years she has revealed to me all the different ways we can employ our other senses. She has an astonishing ability to truly listen to the world around her. She will hear a bird tweet in a crowded space and smile, while the rest of us wonder what is taking her fancy as we share a picnic. The wind blowing towards us in the distance will cause her to tense up (as she doesn’t like the wind on her face) before the rest of us have any sense of what is to come.

The absence of a diverse sensory focus in ADA regulations hinders the creation of emotionally stimulating experiences, to the detriment of all. It’s time for a change. Within the next few decades, we will hopefully see modern materials, technology and improved personal mobility devices increasing access to the outdoors. However, we can take action now to make better use of existing technology to implement infrastructure that goes beyond ADA regulations to engage our wide array of senses, promote diverse experiences and ultimately provide a richer universal outdoor experience for all children.

What does inclusive play look like?

So what might a play area better designed to fit the needs of the disability community look like? Inclusive play areas utilize the concept of Universal Design to promote play among children of differing abilities, ages and levels of confidence or skills. If successful, they give every child the same platform to play by employing numerous sensory experiences to equitably provide a variety of emotional responses and engagement levels. The physical design of a traditional inclusive playground should still include the typical elements of ADA-accessible spaces, such as ramps, lifts, accessible surfaces, parking and bathrooms. However, they differ from other outdoor areas that include ADA accommodations because the goal is to eliminate all physical and social barriers so everyone – children, parents, caregivers and community members – can experience the benefits of playing together.

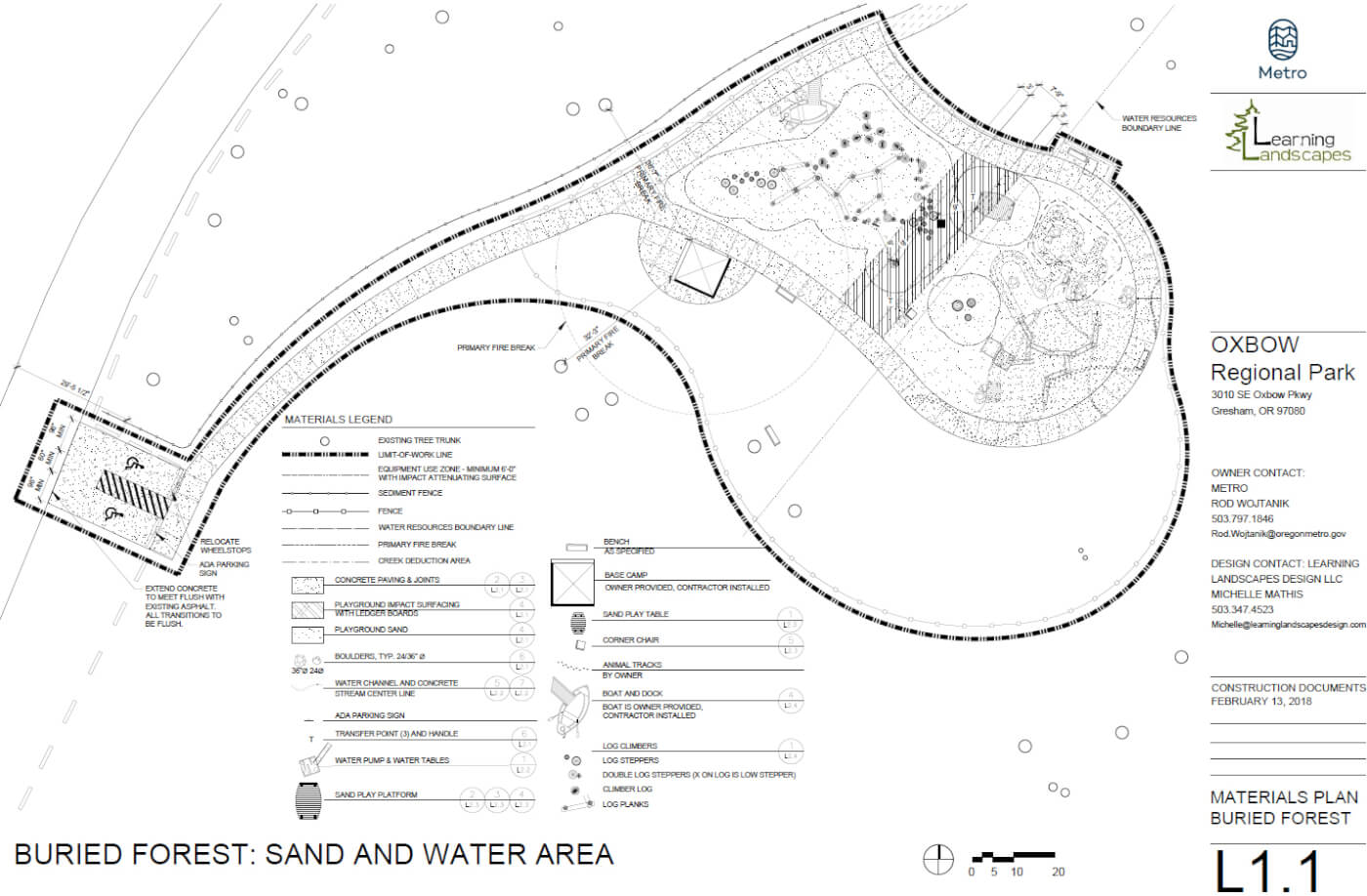

A universal design for a nature play area that was built at Oxbow Regional Park near Portland, Oregon. Photo Credit: Michelle Mathis, Principal Designer, Learning Landscapes.

Inclusive playgrounds feature specially designed equipment, like the Inclusive Whirl, Sensory Wave Climber and Rox-All-See-Saw. These elements are designed to accommodate users of all abilities by enabling easy on/off or transfer to and from a mobility device. They represent a subset of ADA-compliant and inclusive playground equipment that go above and beyond the standard regulations to create an engaging play experience.

When we incorporate nature into the design of playspaces, we can also take advantage of the natural features at a site including hills, trees, creeks and more. It is important to note an inclusive play area (both prefabricated and one that incorporates nature play) does not simply place ADA-accessible equipment in a particular part of the park. Instead, accessibility should be infused throughout the design, creating a sense of belonging and kinship.

Incorporating “Wellness by Design” at Boulder Parks and Recreation

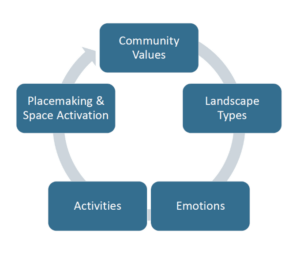

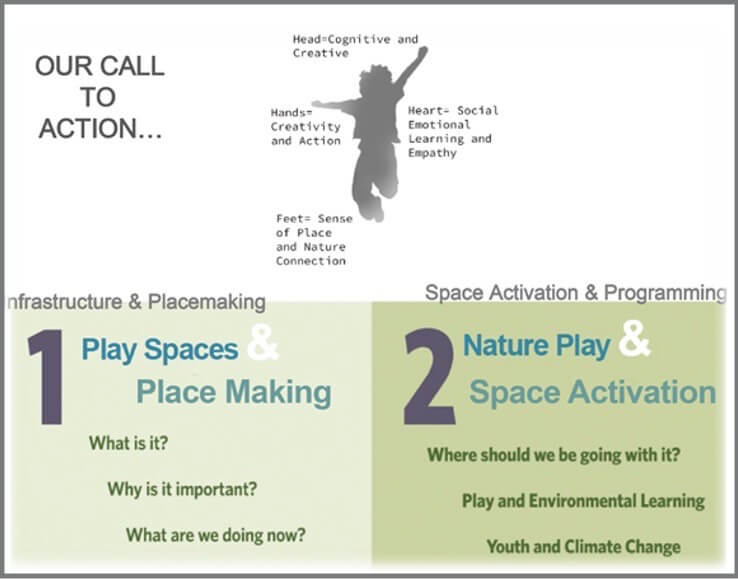

At Boulder Parks and Recreation, we want to enhance our intentional design process by actively promoting placemaking (related to the physical layout of a place) and space activation (related to recreational activities and programming within that space) in inclusive playgrounds. This has led us to the development of an iterative approach that we call “Wellness by Design.”

The Wellness by Design cycle aims to create feelings of belonging and a sense of place.

As part of the Wellness by Design process, we must first examine the emotions of youth and the sensory inputs that inform those emotions to build a picture of how youth perceive and respond to both the built and natural environment around them. In the disability community, this can be very informative as neurodiversity creates responses that may surprise folk. Lydia responds with pure joy when she hears children shouting at the top of their lungs, yet the sound of a swing creaking will cause a seizure that will be followed by tears. The task of meeting everyone’s needs within the disability community is nearly impossible, but the goal is to understand how we can best meet as many needs as possible.

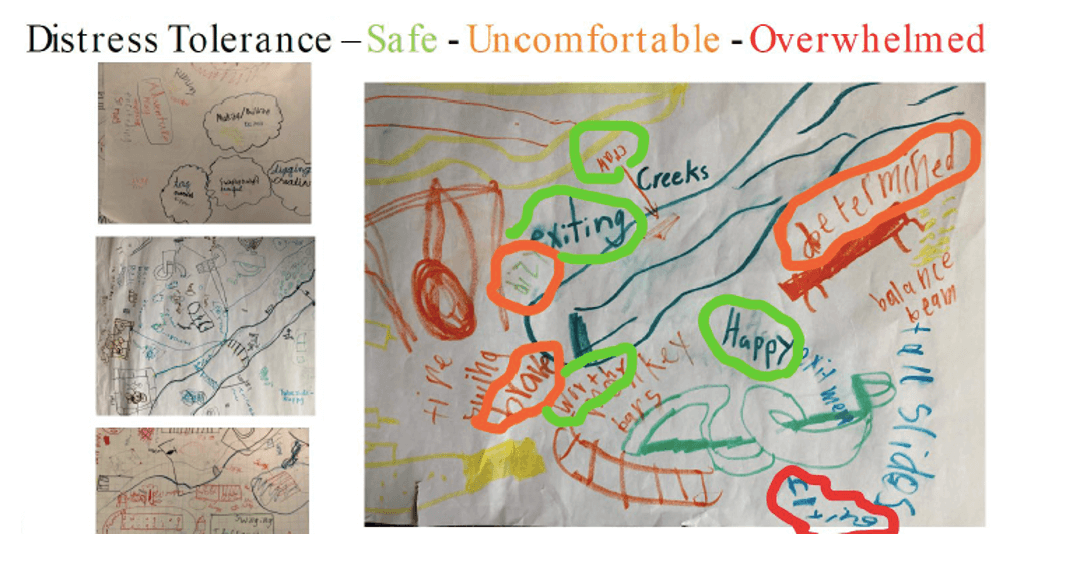

For example, when youth were tasked with conceptualizing an imaginary park and defining both activities and emotional responses, we analyzed their responses to see what felt comfortable, uncomfortable and overwhelming. Uncomfortable spaces are crucial for learning, and their absence can lead youth directly to feelings of overwhelm. In the context of the disability community, creating uncomfortable spaces is particularly vital for learning and therefore important to our design plans.

Children drew and designed their favorite activities and associated emotions for a new park. The analysis maps the emotions in terms of what feels “safe”, “comfortable” and “overwhelming”. Learning occurs mostly in the uncomfortable zone, a space we often prevent children from entering due to an unintentional yet misguided sense of perceived safety issues.

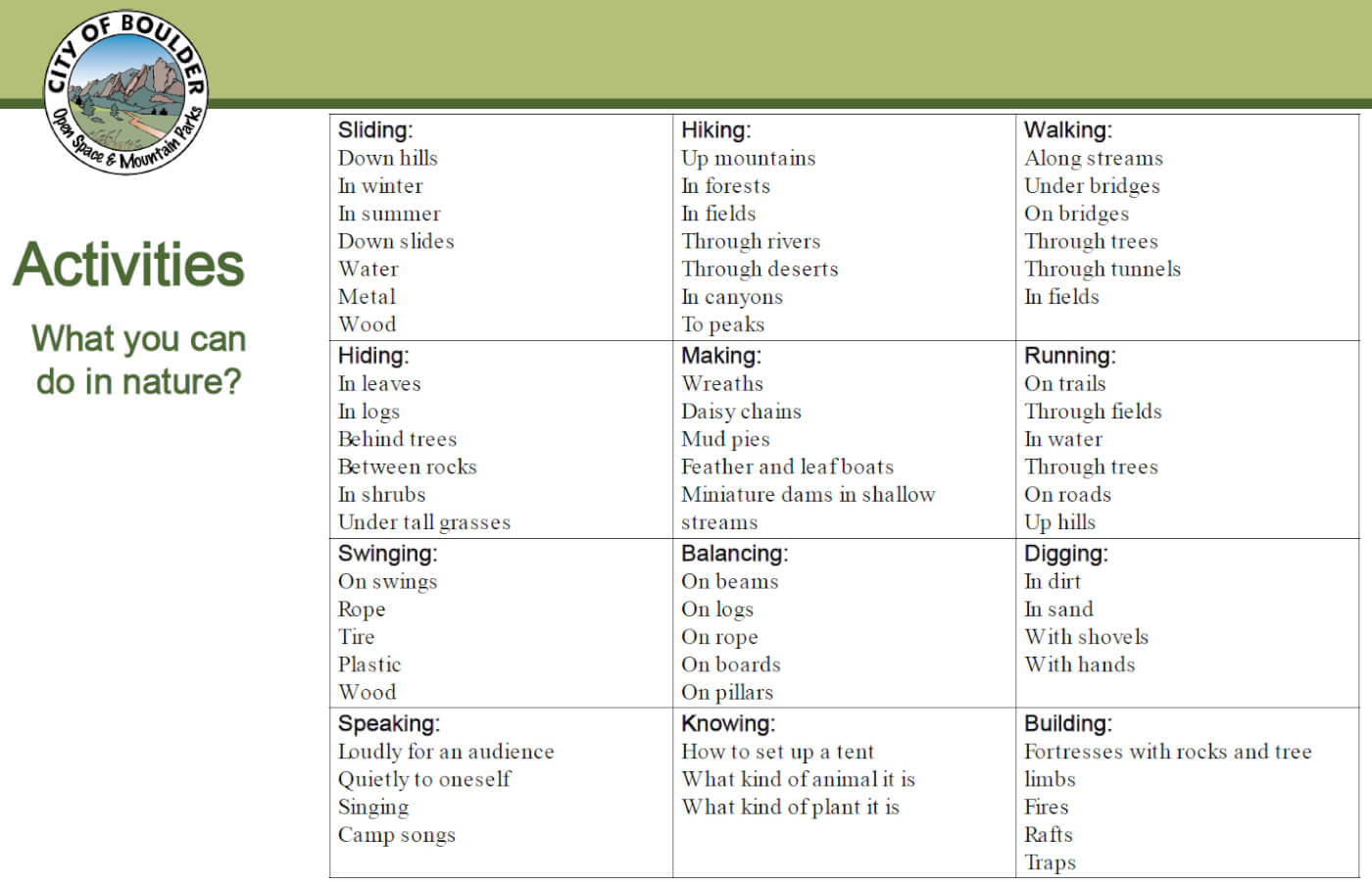

Next in the Wellness by Design process, we identify the sensory inputs and emotional responses we want to evoke in an inclusive playspace and connect them with activities. This can be done by examining a list of play activities and then identifying how each of those activities might occur. For example, “climbing” can include climbing a tree, a climbing frame, a boulder, or collaborating as a team with hands and shoulders to get on top of something.

Example of play activities and associated ways they can be designed for or make use of the natural environment. Courtesy of City of Boulder.

Finally, subsequent efforts in placemaking and design are guided by these identified emotions and activities, as well as community collaboration. Input from the community is integral to understanding the specific characteristics of the place, and the values and importance the community associates with the space. Targeted recreation activities and associated programming will activate the space in the future and help both parents and children engage in comfortable and uncomfortable experiences alike.

Through this iterative process, a design emerges that not only aligns with community hopes and needs but is also well-suited for creating universal designs. Ultimately, the “Wellness by Design” approach can be distilled into seven guidelines:

- Enable a diverse sensory experience to engage a wide range of children and youth experiencing disabilities. For example, play areas with more sounds and lighting that encourage different types of play.

- Ensure the sensory inputs provoke emotional responses across a diverse range of the spectrum covering not just comfortable emotions (joy, peace, curiosity, etc.), but also uncomfortable emotions (nervous, sheepish, fragile, etc.)

- Balance the inclusion of uncomfortable emotions (which are critical for learning) with the creation of a space that isn’t overwhelming.

- Don’t prioritize safety over experience within the design. Prefabricated play structures have a higher injury rate than natural play areas. If children can take responsibility for their actions, their play becomes inherently more safe as they learn skills.

- Include a wide range of activities for children’s play through the consideration of diverse sensory inputs and resulting emotions. The activities can engage children in collaborative, competitive or singular tasks covering both physical and mental skills.

- Reverse typical design practice by conceptualizing structures based on the desired activities. The list of activities and their preferred locations guides the design of the play structure. For instance, a hiding activity can take place behind a boulder, in a pile of leaves, inside a structure or collectively behind trees.

- Enhance the accessibility of play areas through thoughtful adjustments and additions to create a more welcoming environment. For example, increase disability parking spaces for rear ramp vehicles, incorporate letterboards or braille signs alongside standard signage and include changing tables in bathrooms capable of supporting young adults up to 100 pounds.

Boulder Park and Recreation Department’s call to action for an integrated approach to placemaking and space activation. Courtesy of City of Boulder.

Universal Design in practice

As a family, we frequently dash out onto our porch to watch Colorado’s beautiful sunsets. However, this often leaves Lydia inside the house and it was once painful for me to think that Lydia would never experience a sunset like the rest of us. The teachers at Anchor Center, Lydia’s wonderful preschool, had other ideas. They worked hard to increase Lydia’s Cortical Vision Impairment (CVI) from a 1 out of 10 (virtual blindness) to 3 out of 10 (she could see outlines, shadows, color). One afternoon in class when we were using a light board a teacher had built, I watched as Lydia’s eyes pricked up and she followed the rainbow of lights moving from left to right across the board. I cried silently, tears flowing down my cheeks. Lydia was watching her version of a sunset, and she gave me one of her huge smiles as the pattern repeated. Sunset after sunset.

These accommodations for Lydia, custom-made and thoughtfully devised, are what true universal design looks like. It’s not easy. People will constantly tell you that universal design is too complicated. You have to be persistent, you have to get back up again, each time the barriers knock you down. Why? Because despite all the time it took to enable Lydia to see her sunset, every drop of hard-earned sweat fades away when I get to see her connected to the world around her, belonging, a whole person, with such love that she is willing to share with our community.

Play area design concept by Momi Davison, age 6, with design detail in top right showing an accessible tree house.

Universal design doesn’t have to be complicated or expensive. When you break the process down to consider what emotions you hope to elicit and the associated activities, the design opportunities become endless. Below is a short list of examples that hopefully will inspire you to go beyond ADA into a universal world where all children are accepted and their lives enriched equitably:

- Think of play as an activity children do, not the thing they play with.

- Add letterboards at entrances to play areas (even if not used, they indicate that a place is welcome to children with disabilities)

- Include a flat, round group swing (Lydia will lie in the middle with her two siblings on either side to protect her)

- Offer large changing tables that have a privacy screen

- Plant multiple sensory elements that are both loud and subtle

- Distribute play pods around a path (1/4 to 1 mile) to provide opportunities for both collaborative and singular quiet play

- Incorporate nature play, rather than prefabricated equipment, which increases opportunities for universal design

- Create quiet spaces where children can rest, observe others, be alone (Lydia loves to relax on her back, flat against the soft bare earth to watch a gentle wind push tree bows as dappled light flickers through the weaving patterns created by the leaves)

Photos capturing Lydia living life to the fullest extent with the support, playfulness and ingenuity of a community who love her for who she is and think of disability as a natural part of everyday life.

There are still days when it takes our family up to 2 hours just to get out of the house and into the car with our three kids, assistance dog and all the equipment Lydia needs. At some point, one or two of us will normally give up, but there is always someone else willing to offer words of encouragement to keep us going. As a family, we have emerged through our experiments in parks and nature with a fistful of tools to play, communicate and enjoy life together. And whenever we finish an outdoor activity together, we look back with a sense of pride and contentment that Lydia’s disability can be a part of everyday life.

With community and family support, she is an included, independent member of our community. Creating more opportunities for other children with disabilities and the parents or caregivers who support them to spend time in nature through intentionally designed outdoor spaces, like inclusive play areas, is crucial. With universal design, we have a path forward. If we let our playful selves travel along it, the path will lead to more equitable access to nature’s many benefits – and I’m thankful for Lydia, for showing me this truth.

7 Comments

Submit a Comment

-

Feature

GROWING POWER: Urban Roots connects young people with natural spaces, food systems – and one another

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Network News

Community Spotlight: Prescribe Outside

-

Richard Louv

SPRING FORWARD! 12 Ways to Make Sure Your Kids (and You) Get the Right Dose of VITAMIN N this Spring — and Summer, Too

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

Mark thank you for sharing Lydia’s story with us, and for all that you do to create inclusive play so that all children of all abilities can connect with nature.

Thanks Mark. Seeing your distress tolerance mapping of playgrounds took me back to collaborating w you on and doing a kind of experiential linear mapping of the Stevens Canyon Highway on Mount Rainier so many years ago. Your family and the City of Boulder are lucky to have you. Keep up the good work!

The world needs more insightful, elucidating articles like this that remind us of what we often take for granted, and more often, fail to understand and appreciate about the experiences of all those around us. Thank you for sharing, and keep up the important work of both sharing your unique family experiences and designing parks, trails, and more accessible areas for all to enjoy. Props to your service and contributions to the

Thank you for sharing your experiences and expertise, Mark. In Austin ISD, we are working hard to incorporate universal design in our new projects. I am especially interested in bridging the needs for nature connection and sensory rich natural environments with inclusive design. Looking forward to sharing this with colleagues, and learning more from you at the conference in Madison!

What a beautiful story! Thank you for sharing, Mark

An important aspect of thoughtfully creating spaces for people who experience all kinds of differences is that typically developing people have more opportunities to observe and interact with them and experience how normal disability is.

Another significant consideration in creating natural environments is to plan for people with temporary disabilities who do not have the know-how gained through lived experience or the expensive equipment (such as a low-slung, transit-safe, modern wheelchairs) of those with permanent disabilities.

Kids, with and without neurodivergent conditions, become disabled after surgeries or injuries, and being able to still access play spaces and areas they are used to in their ordinary lives helps reduce the impact of sudden, dramatic changes to their previous abilities.

I absolutely love this…everything about it. Your passion. Your vision. Your story. Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!

My sister in law just accepted a job with Parks and Rec in the San Diego area. I’m forwarding this to her.