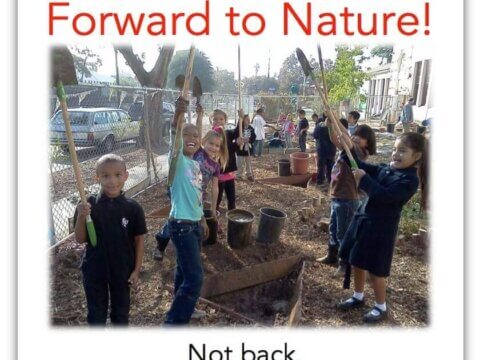

The New Nature Movement Isn’t About Going Back to Nature, but Forward to a Nature-Rich Civilization

This column is adapted from an essay that originally appeared in the book, “Thirty-Year Plan: Thirty Writers on What We Need to Build a Better Future,” published by The Orion Society, 2012, in which writers imagine the future. These ideas are explored in greater detail in Richard Louv’s 2011 book,” The Nature Principle.”

For many people, thinking about the future conjures up images from movies like Blade Runner, Mad Max, The Road: a post-apocalyptic dystopia stripped of nature and human kindness. We seem drawn to that flame, but it’s a dangerous fixation.

There are many reasons for the attraction – global threats to the environment, economic hard times, decades of disconnection between children and nature – but there’s a fundamental problem with it too. Martin Luther King. taught us that any movement — any culture — will fail if it cannot paint a picture of a world that people will want to go to.

Despite undeniable successes, environmentalism is in trouble: recent polls (many, not all) describe a public with diminishing regard for environmental concerns. What we need now is a new nature movement, one that includes but goes beyond the good practices of traditional environmentalism and sustainability, one that paints a compelling, inspiring portrait of a society that is better than the one we presently live in. Not just a survivable world, but a nature-rich world in which our children and grandchildren thrive.

Despite undeniable successes, environmentalism is in trouble: recent polls (many, not all) describe a public with diminishing regard for environmental concerns. What we need now is a new nature movement, one that includes but goes beyond the good practices of traditional environmentalism and sustainability, one that paints a compelling, inspiring portrait of a society that is better than the one we presently live in. Not just a survivable world, but a nature-rich world in which our children and grandchildren thrive.

Inchoate, self-organizing, this new nature movement is already beginning to emerge.

It revives old concepts in health and urban planning (Frederick Law Olmsted, Teddy Roosevelt, and John Muir come to mind) and adds new ones, based on recent research that shows the power of nearby nature and wilderness to improve our psychological and physical health, our cognitive functioning, and our economic and social well-being. Colorado University professor Louise Chawla describes the basis of the movement as “the idea that as humans we cannot only make our ecological footprints as light as possible, but we can actually leave places better than when we came to them, making them places of delight.”

Among the movement’s tenets, which I suggested in The Nature Principle: The more high-tech our lives become, the more nature we need. Cities must become engines of biodiversity. Natural history is as important as human history to our regional and personal identities. Conservation is no longer enough; now we must “create” nature where we live, work, learn and play. Likewise, energy efficiency isn’t enough; now we must create human energy — in the form of better physical and psychological health, higher mental acuity and creativity — by truly greening our cities.

This movement isn’t about going back to nature, but forward to nature. Participants include traditional conservationists, as well as proponents and producers of alternative energy, who create the underpinning. Physicians (particularly pediatricians) who prescribe nature experience and green exercise to their patients. Ecopsychologists, wilderness therapy professionals, and other nature therapists. Park professionals who help families fulfill their “park prescriptions.” Public health professionals and urban designers who work to increase nearby nature.

Also: Citizen naturalists who are salvaging threatened natural habitats and creating new ones. New Agrarians: community gardeners and urban farmers (including immigrants practicing what has been called “refugee agriculture”); organic farmers and “vanguard ranchers” who restore as they harvest. Urban wildscapers replacing their suburban yards with native species (slowly creating what botanist Douglas Tallamy calls “a homegrown national park.” Nature-aware champions of walkable cities and active living. And deep green design professionals: biophilic architects, developers, urban planners, and therapeutic landscapers, who transform our homes, workplaces, suburbs, and inner-city neighborhoods – potentially whole cities and their transportation systems – into restorative regions that reconnect us to nature.

Also: Citizen naturalists who are salvaging threatened natural habitats and creating new ones. New Agrarians: community gardeners and urban farmers (including immigrants practicing what has been called “refugee agriculture”); organic farmers and “vanguard ranchers” who restore as they harvest. Urban wildscapers replacing their suburban yards with native species (slowly creating what botanist Douglas Tallamy calls “a homegrown national park.” Nature-aware champions of walkable cities and active living. And deep green design professionals: biophilic architects, developers, urban planners, and therapeutic landscapers, who transform our homes, workplaces, suburbs, and inner-city neighborhoods – potentially whole cities and their transportation systems – into restorative regions that reconnect us to nature.

None of these ideas is truly new. For examples and precedent, we can look to earlier social movements, including those which promoted healthy cities and nature studies in the early 20th century, as well as those forwarding civil rights and feminism, and the current movement to connect children to nature. This recent worldwide movement, which the Children & Nature Movement is helping to build, can be seen as both a model for and a subset of a larger new nature movement.

In September 2012, the World Congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) passed a resolution declaring that children have a human right to experience the natural world, an essential ingredient if nature is to protected from human excess — and a step toward seeking a similar declaration at the United Nations. At the same World Congress, leaders of national parks and protected areas throughout the world approved the “Jeju Declaration on National Parks and Protected Areas: Connecting People to Nature,” committing them to create a global campaign that recognizes the great contribution of these natural treasures to the health and resilience of people, communities and economies.

The children and nature movement has miles to go before it can declare anything approaching victory. But it has already made inroads in policy and, more importantly, has planted the seeds for self-replicating social change,, including at least 109 regional and state campaigns that have brought together businesspeople, conservationists, healthcare providers and others. These others include thousands of parents, teachers, law enforcement officials, librarians, artists, pediatricians, liberals and conservatives, anglers, hunters, and vegetarians. People who not only consume, but also restore nature. People who have found common cause. The children and nature movement, like the larger new nature movement, is surprisingly diverse. Recent immigrants, and inner-city youth, are among the most persuasive advocates for nearby nature and outdoor experience — once they get a chance to have such experiences.

Not all of the individuals and groups I have mentioned would identify themselves as environmentalists. They do not necessarily see themselves as part of one movement – yet. But consider the collective power if these forces came together to craft a positive vision of the future, a newer civilization based on a transformed human relationship with the natural world. We certainly don’t have to agree on everything to reach that goal. But we must agree that our species’ connection to nature is fundamental to our shared humanity — and to the future of Earth itself.

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement

Commentaries on the C&NN website are offered to share diverse points-of-view from the global children and nature movement and to encourage new thinking and debate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of C&NN. C&NN does not officially endorse every statement, report or product mentioned.