Across Perú, Tierra de Niños (Children’s Lands) create deep connections to nature for students and communities

“Every child should have a little garden, a little place where they can love Mother Earth, and be loved by Mother Earth,” says Joaquín Leguía, founder of ANIA, a Perú-based NGO working to promote sustainable development and active empathy for the natural world through programs that connect children to nature and empower them as agents of change.

A key initiative of ANIA is to develop and support Tierra de Niños (TiNis), or Children’s Lands. TiNis are child-led, nature-filled spaces where children learn to nurture life and biodiversity by planting and caring for gardens and outdoor spaces for learning, restoration and play. “TiNis enhance the well-being of children, their communities and the planet,” says Leguía. “Children begin to see Mother Earth as a teacher and an ally.”

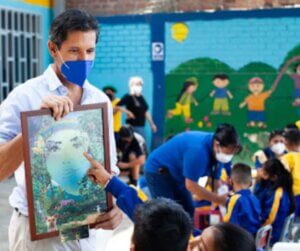

ANIA founder Joaquín Leguía and students celebrate Mother Earth as a teacher and an ally. In the Andean-Amazonian worldview, all life comes from Mother Earth, which is viewed as a being, not a thing. Photo courtesy of ANIA.

Found in schools across Perú, TiNis can also be created at home and in neighborhoods, in urban and rural areas, and in ecosystems ranging from Lima’s Pacific Costa Verde, to the high deserts of the Andes Mountains, to the Amazon rainforest. The flexible model works for schools that have access to large natural areas – and for those with very little space in dense urban areas. TiNis do not require large development budgets; they are often constructed from found objects, scrap wood and recycled materials. Colorful coats of paint turn wooden pallets into charming picket fences and “canvases” for children’s art; cans, plastic bottles and rocks are transformed into butterflies, ladybugs and other garden friends; and seeds harvested from native plants bring TiNis to life.

Best practices to inspire the field

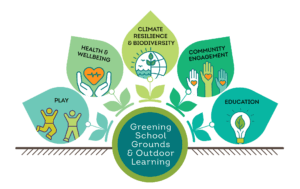

In 2022, the Children & Nature Network and a group of international partners launched Global Lessons on Greening School Grounds & Outdoor Learning to identify successful approaches and scalable strategies for creating nature-filled school grounds. The initiative will share case studies and best practices from 13 unique locations around the world.

“ANIA’s work in Perú was selected for study because the TiNi methodology is highly adaptable, making it replicable and scalable,” says Jaime Zaplatosch, Sr. Vice President for the Children & Nature Network (C&NN). “Another key factor is that TiNis are child-led – something you don’t find very often when it comes to planning school grounds.”

“TiNis are a wonderful example of how greening school grounds can enhance children’s play, health and well-being – and improve climate resilience, biodiversity, community engagement and educational outcomes,” continues Zaplatosch.

The benefits of green school grounds and outdoor learning

A look at TiNis in Perú

ANIA, founded in 1995, created its first Children’s Forest in the Amazon jungle on 10 hectares (25 acres) of land donated by the community. “The concept began to thrive and people started hearing about us,” says Leguia. “TiNis began to spread across Perú, from the jungle, to the mountains and on to the desert and the cities. Soon we were training people in Bolivia and Brazil and many other countries.” In 2012, TiNis were recognized by UNESCO as a best practice in education for sustainable development. By 2015, the Peruvian Ministry of Education had adopted the TiNi methodology and in 2017 the ministry of education of Ecuador did as well. And according to ANIA, “in 2020, before Covid, there were more than 2 million children contributing to the regeneration, sustainable use and care of more than 2.5 million square meters of land.” Today, robust TiNi programs can be found in 10 nations ranging from Colombia to Canada to Japan.

We visited TiNis in three regions of Perú: Iñapari in the Amazon Basin; Chincha, in the arid Chincha Valley; and the Lima metropolitan area on the Pacific Coast.

Villa Primavera Primary School, near Iñapari

Students observe a bright orange caterpillar in the outdoor classroom next to their TiNi. “No toca (don’t touch),” they warn us – based on their extensive knowledge of plants, insects and wildlife in the Amazon. Photo: Jaime Zaplatosch

“Coo-coo, coo-coo,” children call to each other up and down the trail as they head to their forest classroom. Along the way, they identify plants, trees and their uses. These young naturalists typically start their school day by tending the vegetables, flowers and fruit trees they’ve planted in the TiNi next to their one-room schoolhouse, which serves a dozen or so students ages 6-11 from Villa Primavera, a small village near the town of Iñpari on Perú’s border with Brazil and Bolivia. It is one of the most biodiverse regions in the Amazon. Lessons are often held outdoors in the school’s thriving, plant-filled TiNi – and 2 to 3 days each week, students head into the rainforest, using trails they and their families help maintain. Ask any student their favorite thing about school and without exception, they all say, “el bosque” (the forest).

A 200-year old shihuahuaco tree is a natural jungle gym. Photo: Jaime Zaplatosch

The benefits of outdoor learning are well-documented, but there’s nothing quite like seeing it first-hand, as our C&NN team did while visiting TiNis with ANIA’s founder Joaquín Leguía and program manager Anyela Gómez. “Seeing children’s enthusiasm for learning, their knowledge, and the way they interacted with the forest, their gardens and each other was incredible,” says C&NN Green Schoolyards Program Coordinator Brenda Kessler. “I kept thinking to myself, ‘How can we make this available to all children?’”

The TiNi at Villa Primavera’s primary school has benefited the community as well as the students. “Before the children and their families got involved with the TiNi, there was a saying that translates roughly to ‘the forest eats everything,’” says Gómez. Villagers would dispose of junk and garbage in the forest because it would “disappear” in the undergrowth. Today, the village not only prevents illegal dumping in the forest, they protect the trees, plants and wildlife. Some families are even creating mini-TiNis in their homes. “TiNis inspire people to think about the forest differently, to care for the natural world around them,” continues Gómez.

Sign at the entrance of the forest classroom trail in Villa Primavera reads, “Our agreements: Pick up your garbage, take care of the animals, don’t start fires, do not cut the trees.” Photo: Jaime Zaplatosch

Chincha Primary School, Chincha Alta

Primary school TiNi in Chincha. Photo: Laura Mylan

The city of Chincha is located in one of the largest valleys in the Pacific coast region, surrounded by desert. The streets of this vibrant community are dry and dusty, but stepping into the courtyard of the local primary school is like stepping into another world. Lush gardens, designed and tended by students, create a nature-filled oasis. Children spend part of each day in classrooms circling the courtyard, and part of each day in their TiNis; each class has their own designated garden space. School director Maria Soledad Ochoa Pochas says, “When [the children] come out here, their brains are engaged. You can see the impact on their learning. Their minds become playful, and full of questions. They get involved in caring about the environment. It’s wonderful.”

We produced a Facebook Live broadcast from Chincha; view the recording here.

Villa Clorinda Primary School, Lima metropolitan area

Students caring for their TiNi. Photo: Laura Mylan

At Villa Clorinda’s primary school on the outskirts of Lima, students walk from the dusty hillsides to a TiNi bursting with plants and children’s art. Like many TiNis, brightly painted recycled materials – cans, old tires, scrap wood – bring color and life to the school yard.

Children walk from the surrounding hillsides to their school-based TiNi, filled with color and life. Photo: Laura Mylan

One of the things we heard on all of our school visits was how much joy TiNis bring to both students and teachers. Families benefit, too, often volunteering to help in the TiNi. Kiara, a 12-year-old student, says that “being part of this program at my school and at home has allowed me to be part of a greater change to care for the environment and our planet.” And in this particular school, teachers have made the TiNi methodology their own, creating environmental superhero characters to make their classes fun and engaging.

Teachers at the Villa Clorinda Primary School incorporate self-made environmental “superhero” characters to enliven environmental education for young students. Photo: Laura Mylan

While touring TiNi’s in Perú, we produced a short video case study, with the help of some young production volunteers. You can view the video on our Global Lessons on Greening School Grounds & Outdoor Learning webpage.

Students from Villa Primavera assist with a sound check. Photo: Laura Mylan

-

Network News

Earth Day: Young leaders advocate for change

-

Feature

Nature photographer Dudley Edmondson has a vision for the representation of Black and Brown faces in the outdoors

-

Richard Louv

EARTH MONTH: You're part of the New Nature Movement if....

-

Voices

Placemaking: How to build kinship and inclusive park spaces for children with disabilities

-

Network News

Children & Nature Network founders release report on global factors influencing the children and nature movement